First time it happened, I was early to the gym and alone in the ring, waiting on my trainer to hit the mitts. Hands wrapped, gloves slung over the ropes, killing time with some shadow boxing. And then I heard him.

The strum of a guitar, a guttural hum, the raw edges of what sounded like the start to a song, maybe the makings of another masterpiece that I’d be the first person in the world to hear. I dared not turn around. I’d been schooled. You don’t look a god in the eye and you never bother the owner of the gym, ever.

Then my trainer arrived, threw down his massive gym bag, and greeted us both: Hey LG (my uninspired ring name). Hi Bob.

Bob looked up from where he sat on the edge of the couch, looked at me as if I’d just materialized, nodded at the trainer, and without a word took his noodling to another room. I understood. Bob Dylan doesn’t play solo concerts for just anyone.

Maybe my coolest cocktail party anecdote: For more than a decade, I trained and sparred at a small, private boxing gym owned by the man himself.

So many of the highlights - and lowlights - of those years happened for me there, in the shadow of his legend. It’s corny, but true. Dylan’s little ring, with its animal print carpet, chair shaped like a huge high heel shoe, and walls lined with posters and paintings of boxers, gave me shelter from my storms. The invitation to come inside was one of the luckiest of my life.

(No, the ask didn’t come from him. Moved to L.A., met a woman who turned out to be best friend’s with the manager of the ring, went to a birthday party on the property, chatted up some seriously fit and tough women who turned out to be boxers, and by the following week I was learning to throw punches.)

Back then, I did not speak a word of this to outsiders. Ring rules were implied but clear: You do not discuss Dylan. Also, after a while, it stopped seeming like such a big deal. You’d enter through a back door designed to look like a delivery entrance and wait to see if you smelled cigarette smoke, the telltale sign that the boss was in the house, where he also kept an office. If you happened to pass him in the corridor, decorated with signed vintage photographs of boxers and musicians, you knew not to engage unless engaged. But really, we were there to box. All of us shared the same trainer. Bob, too.

Not surprisingly, the man who wrote “Hurricane” boxed – and yet that’s the part of the Bob Dylan-owns-a-boxing-gym story that most surprises people. I only witnessed this a time or two, and I’d describe his style as shambling but effective, if only because I’m pretty sure his sparring partners weren’t allowed to smack him back, certainly not full force. I’d swear I once saw him wearing street clothes in the ring. No matter how hard I try, to this day I can’t picture Dylan in T-shirt, shorts or boxing shoes.

I’m not trying to pretend I was anything more than on the edge of his world, and mostly deemed unworthy of interaction. Encounters were few and very far between. For starters, I liked to train before work, early hours I imagine Dylan hadn’t seen in some time. But also, it was L.A. Dylan’s gym, and the wildly effective trainer, attracted actual movie stars and industry shakers. I was just a lowly bureau chief for The Boston Globe, able to fight the fight but not to talk the Hollywood talk. I had no interest in it anyway. I was there to work out and work my way up to four rounds (protected by head gear and a chest guard, of course).

Googling “Bob Dylan boxing ring” now, I see that writer/director Peter Berg (ring name Dirty Pete) has since talked about training there, and shared how much the late great comedian Gary Shandling (G) loved boxing with the boss. (Once, while in the ring with Shandling, I made a joke. He laughed. I was thrilled. Then he tentatively asked, “I’m funny, too, right?” He was not kidding, making him the most-like-his-TV-self actor I’ve ever met, and also one of the sweetest.) I also see Ben Stiller has spoken about fighting Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini at the gym, which brought back the time I was hitting the bag beside Mancini, who I didn’t recognize. For some reason, I decided I had the perfect ring name for him and offered it up. “Um, I have one already,” he said, and, ever the gentleman, never mentioned this moment again. Quentin Tarantino was a regular before my time (a woman I befriended there and who later threw my baby shower once knocked him down), and one time I hit David Duchovny (Double D) so hard in the face by accident that I feared I’d broken his nose.

Still, even in Los Angeles, maybe especially in Los Angeles, there was this famous person and that more famous person and then there was Bob Dylan, in a hierarchy all his own. He was a mystery to me the entire time and I liked it that way. His eccentricity seemed a necessity of his genius, and the quiet he generated gave me some odd sort of comfort. Setting aside the pugilistic aspect of it all, this place he’d created was such a sanctuary for me.

Dylan’s little gym 18 blocks from the beach in Santa Monica was tucked, hidden really, behind a café he also owned and which, it should almost go without saying, had a vintage jukebox stocked with a fantastic, eclectic selection of music. There were hand-tiled tables, a checkered floor, and two humongous statues of chefs at the front door, as well as a gorgeous patio garden. There was also no internet service and no cell phones allowed. Dylan, I was told, believed that creatives should create, not scroll Twitter, answer emails, or interrupt artists with their chatter. Dylan was also landlord to a synagogue, which held services on the opposite side of the building.

All of that appears to be closed and gone now; the doors locked, the windows dark, the parking lot empty. I drove by recently to make sure, since I hadn’t thrown a punch there in eight years. I did hear that after Dylan and our trainer had a falling out, most everyone I knew moved on to other rings or workouts. The long moment in time that was boxing at Bob Dylan’s private gym passed.

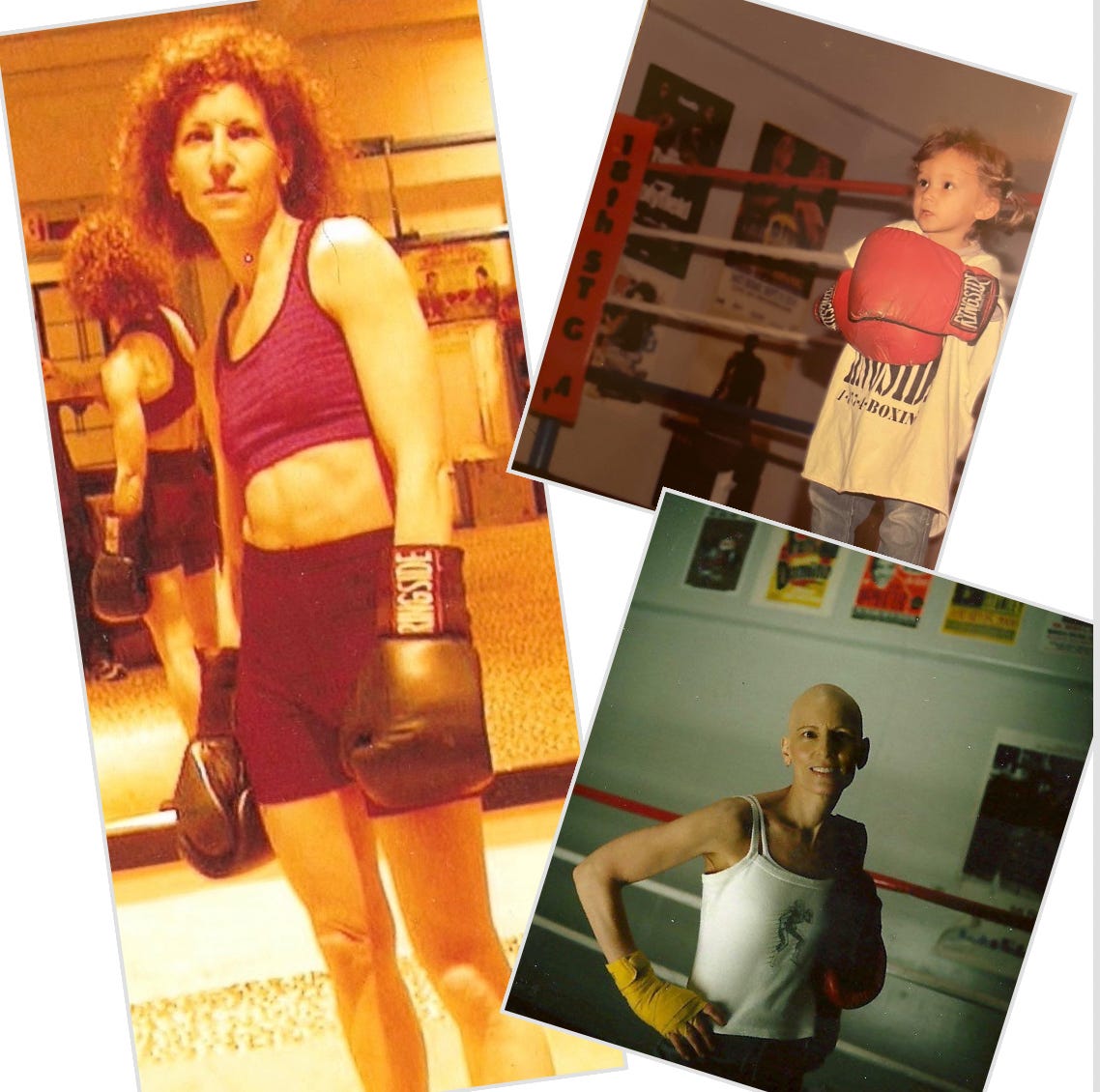

It's wild to think now how much of my time was spent there and how much happened to me there. My hands were still wrapped when I stepped out of the ring to take a call from my ob-gyn, who told me a test had unexpectedly turned out positive for pregnancy. Nine months and change later, I’d set my daughter’s baby carrier against the ropes and try to focus on getting my body back. Two years after that, I got word that I had breast cancer and headed straight over to hit the bag. The ring was the first place I let anyone see my newly bald head, and I trained through almost a year of treatment. The week I finally finished radiation, weighing 95 pounds tops, the lovely woman who ran the operation for Dylan called to say, “Bob has two concert tickets he can’t use, do you feel like celebrating?” That’s how a friend and I ended up so close to the stage that I worried the amazing Aretha Franklin’s ginormous breasts would swallow scrawny me whole as she belted out hit after hit.

All that said, I am far from a Dylan fanatic. I know a lot of his music but not the entire oeuvre by any stretch. I’m not obsessed with him as a musician or a man, although of course I’ve seen him in concert. I’m still weighing whether to see the biopic “A Complete Unknown,” about Dylan’s early days of fame, which took place about 35 years before I first climbed into his ring. That would have been 1997 or so, and he was already in his mid-50s by then.

Thing is, the Dylan I knew – and I use the word “knew” incredibly loosely here - was exactly what you’d expect a boy genius to grow up to be: more than a little complex, a lot quirky, seemingly a shy loner but also entirely self-aware of his stature. His son Jakob (of “and the Wallflowers”) was such a smiling, easy-going presence by comparison. Then again, I’m guessing he didn’t have overly devoted fans like the ones who’d somehow sussed out his dad’s connection to the place and would stake out the parking lot.

One of the only times I remember Dylan speaking to me directly was when I was assigned to Afghanistan in the aftermath of 9/11. In the days leading up to departure, I worked out my anxiety at his gym. Wanting to go to a war zone and being terrified are not mutually exclusive. Hitting something helped. Someone must have mentioned this to him, or maybe he heard people talking. When we crossed paths, he mumbled what sounded like, “Take care of yourself.” The next time I saw him, which was by then 2003, I think he might actually have smiled at me. Or maybe not.

To this day, my daughter, who grew up watching mom pull on boxing gloves and had a tiny pair herself by age three, will hear a Dylan song come on the radio and say, “Oh, it’s Bob from the gym.” My daughter is now 22. Life moves on. I’ve moved on to Pilates. My days at Dylan’s secret gym will live in me forever.

Dear Lynda, I've known you for a long time and you never mentioned Bob Dylan's Gym. You've done a great job of keeping those experiences hidden... until now in a story. No mention, even when the photo of you in your boxing gear with a bald head appeared on the cover of a magazine.

Thanks for sharing this fascinating story!